1.

Please summarize your organization’s overall stance on comprehensive scarcity pricing proposals.

Energy Division staff (ED staff or staff) of the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) develops and administers energy policy and programs to serve the public interest, advises the CPUC, and ensures compliance with CPUC decisions and statutory mandates. ED staff provides objective and expert analyses that promote reliable, safe, and environmentally sound energy services at just and reasonable rates for the people of California.

ED staff appreciates the opportunity to comment on CAISO’s approach to scarcity pricing in this Price Formation Enhancements Working Group.?In general, ED staff supports incremental and minor adjustments to scarcity pricing due to the major energy market changes already coming with the launch of the Extended Day Ahead Market (EDAM) in 2026. ED staff is concerned that introducing a new scarcity pricing mechanism would create duplicative efforts and unnecessary costs for California, which could negatively impact ratepayer affordability goals. A new scarcity pricing mechanism would likely duplicate multi-pronged California efforts to ensure adequate reliability and capacity resources are readily available every hour of the year to the California energy markets to ensure reliability. Entities within the CAISO BAA have already invested billions of dollars to ensure adequate, safe and reliable capacity is available at least cost to the energy markets. Scarcity pricing is unlikely to result in new physical infrastructure investments that will ensure reliability, nor will it result in additional capacity being made available to the energy markets that is not already provided through the numerous existing mechanisms for ensuring adequate capacity is supplied to the energy markets for potential dispatch during every hour of the year.

The existing processes already designed to ensure reliability that could be impacted by this proposal include:

-

California’s Resource Adequacy (RA) framework requires Load Serving Entities (LSE) to procure specific amounts of capacity to ensure adequate and reliable supply. The current planning reserve margin enforced by the CPUC on all LSEs subject to CPUC jurisdiction is 18 percent above the CEC’s adopted load forecast; in addition, there are several additional percentage points (above 18 percent) of capacity available to serve reliability under a variety of circumstances – including some non-RA eligible reliability resources. Taken together, the amount of California-mandated reliability requirements and additional reliability resources, that will be made available to the energy markets, exceeds 20 percent of the load forecast for every month of the 2026 Compliance year.

-

California’s is already making major investments in supply side and demand side Demand Response (DR) resources to ensure reliability. The CPUC has authorized nearly two billion dollars for the IOUs’ 2023-2027 DR portfolios alone.1 And this does not include DR investments by non-investor owned utility (IOU) LSEs, or the DR that these LSEs procure separately through RA contracts. A subset of DR resources count towards RA requirements, but all DR programs and products support reliability under various conditions.

-

California ratepayer investments in Reliability Must Run (RMR) resources and Capacity Procurement Mechanism (CPM) resources, both procured by the CAISO, are designed to support reliability and ensure that California ratepayers pay for capacity to be available to the energy markets on a daily basis under a variety of conditions.

-

California’s Integrated Resource Planning (IRP) and Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS) programs are both designed to ensure new capacity resources are being planned, procured, contracted, and developed to provide energy and capacity products to the California energy markets. These resources provide a range of reliability benefits to the markets and are largely reported to the CAISO in near real-time through the RA program. Without the forward contracting obligations of the IRP procurement requirements and RPS mandates, these resources would not be developed – which is why scarcity pricing by itself will be unlikely to yield development or retention of resources.

-

California invested significant annual ratepayer costs to retain Diablo Canyon Nuclear Power Plant in SB 846. The plant currently supplies approximately 9 percent of California’s energy production. The CPUC approved $722.6 million to extend plant operations from September 1, 2023, through December 31, 20253, and this year approved $382.2 million4 for 2026 extended operations.

Importantly, any new scarcity pricing should be designed with and appropriately account for these existing elements which can significantly impact price formation in direct or indirect ways.

ED staff recommends the CAISO postpone “comprehensive” scarcity pricing modifications in order to first evaluate the impacts and benefits EDAM actually generates for all market participants, including California energy customers. CAISO expects EDAM to produce diversity and reliability benefits, which if achieved, will reduce the minimal usefulness of any additional reliability benefits that CAISO anticipates scarcity pricing might achieve. If EDAM induces capacity to bid into the CAISO markets, then CAISO markets should have additional capacity bidding in – beyond the capacity provided by the RA program, the non-RA eligible DR and ‘effective planning reserve programs’, and any available capacity not-otherwise under RA contract.

The purpose of scarcity prices is to merely increase the available energy rents for suppliers – which can only go to suppliers that are somehow useful in excess of all forward planning reserve margins. While such extreme events may occur, they should be rare, and there are already mechanisms available for energy markets to far exceed marginal costs on a temporary basis, up to a bid cap of $2,000 per MWh. CAISO should consider analyzing the potential impact of scarcity pricing on costs for California customers and other EDAM BAAs to ensure that any proposed scarcity pricing is not duplicative to existing efforts in participating BAAs. CAISO should provide measurable estimates of how much additional supply – in terms of MWs, source, and reliability – that could be induced by scarcity pricing which would not otherwise already be available because of EDAM, RA, IRP, RPS, non-RA eligible capacity resources, etc.

Overview

Rather than create new scarcity pricing products or mechanisms that may induce a very unlikely and small amount of new capacity during extremely rare events – and yet subject the entire energy market stack to a very high price spike – it would be more effective to reform existing CAISO market mechanisms at this time,?such as the Resource Adequacy Availability Incentive Mechanism (RAAIM) or extend the uncertainty time horizon for the Flexible Ramping Product (FRP) as proposed by the Department of Market Monitoring (DMM).?Likewise, SCE has correctly suggested that the existing EDAM design for emergency assistance could already accomplish the goal of curing supply deficiencies (i.e. attaining additional capacity to bid into the market) during temporary, rare, and difficult-to-plan-for extreme events.

Energy market solutions cannot resolve all the challenges concerning resource constraints and reliability. Energy markets are very effective at optimally dispatching available capacity resources; forward capacity procurement requirements (such as the RA program or RMR/ CPM) are much better suited to ensuring that capacity is developed (and/or retained) and then required to bid into energy markets for optimal dispatch. Scarcity pricing cannot build new resources instantly; it can only provide a high payment to resources during an emergency with no connection to or guarantee that such revenues will be invested in building new capacity to avoid such price spikes from reoccurring. The CAISO market is not the mechanism in which LSEs procure long-term supply and capacity products to provide reliability.?The market is only responsible for managing the dispatch of existing resources. High prices during a scarcity event do not lead to additional construction of new resources. Instead, high prices only serve to extract rents from customers that cannot react in real time to avoid paying. This is because the system is already pre-loaded with the capacity amount established via the planning reserve margin (PRM) set by local regulatory authorities' RA programs.

The legislature has given the IOUs and the CPUC a host of requirements to meet for procurement planning, all of which are completed outside of the CAISO market.?For instance, Pub. Util. Code §454.5(b)(9)(C) requires each utility to “first meet its unmet resource needs through all available energy efficiency and demand reduction resources that are cost effective, reliable, and feasible.”?Other long-term procurement and transmission solutions to increase supply would be more effective than creating new scarcity pricing mechanisms that increase prices for California ratepayers.?In considering scarcity pricing, ED staff emphasizes that market rules that allow for significant high price periods to be sustained would run counter to the best interests of customers.?It has proven difficult, if not impossible, to put breaks on a price spike event in real time; and high prices for even a few days can lead to significant energy costs that will be passed onto customers.

For example, the December 2022 gas price spike events led to $3 billion in additional electricity market costs paid to electricity suppliers in a single month that had to be recovered from electricity customers. (additional costs were borne by gas customers). The additional energy costs did not directly lead to any new gas or electricity infrastructure to avoid future price spikes. (The CPUC has an ongoing investigation (I-23-03-008) into these gas price spikes and the impact on customers.) ED staff therefore encourages consideration of Pub. Util. Code § 345.5(b)(2), which directs CAISO to manage the energy markets in a manner consistent with, “[r]educing, to the extent possible, overall economic cost to the state’s consumers.” In this way, the CPUC, the CAISO Board of Governors, and the WEM Governing Body have a shared interest in implementing solutions that reduce costs for ratepayers wherever possible. ?

Scarcity Pricing

Before moving forward with any new scarcity pricing mechanism, CAISO should fundamentally address:

-

whether scarcity pricing is needed and if so, why;

-

the treatment of California exports during scarcity conditions;

-

and how adjoining BAAs govern their own reserves during periods of both coincident and non-coincident scarcity conditions.

CAISO does not necessarily need to adopt a proposal to ensure market prices reflect scarcity pricing during load-shedding events, unless "scarcity”, i.e. high prices, have a potential to induce additional supply to mitigate a load-shedding situation. For example, if there is a physical outage constraint on the grid, no amount of supply at any price will induce supply. Therefore, load should not automatically seek to pay additional rent to generation above non-scarcity prices if it will not change grid operations. Scarcity pricing should only be used sparingly, only for a limited period, and only if it has a potential to induce / increase supply.

Before consideration of any new scarcity pricing, CAISO should ensure that the CAISO BAA does not experience scarcity conditions due to a prioritization of exports. ED Staff is concerned that WEIM transfers and scarcity pricing mechanisms in CAISO could distort prices and potentially lead to the activation of CAISO BAA reserves – which had been procured for the support of CAISO BAA reliability – in order to support energy transfers to other BAAs. If the dip into those reserves also triggers scarcity prices, then CAISO BAA load would pay high rents merely to support exports. Therefore, ED Staff requests that CAISO clearly explain to stakeholders the order of operations for emergency conditions and activation of load shedding (possibly pointing to the CAISO BAA BPM for system emergencies and noting how it is different from RC West operating procedures, if at all) and requests clarification on the following questions:

There are numerous additional open questions on how scarcity pricing and any proposed measures for the CAISO BAA would interact with and/or account for conditions in and actions taken by other BAAs. ED staff would appreciate answers to the following questions, which were submitted to CAISO by Calpine5 almost two years ago on February 19, 2024, and in our own comments this fall, but remain important and have still not been addressed:

In parallel to the work here, ED staff suggests CAISO discuss any new methods for assessing market conditions outside CAISO markets which could have a profound impact on price formation across the West, including inside CAISO. These questions are important to address now, especially since we must determine how to measure when each EDAM BAA has exhausted its reserves. During both the November 10 and 20, 2025 working group meetings, CAISO explained that a scarcity pricing design must include, “A scarcity metric/trigger – a measure to detect when available resources no longer meet system needs.” ED Staff recommends defining reserves or “available resources” broadly to prevent over-procuring of resources. ED Staff therefore recommends that CAISO count all available reserves, both in-market and out-of-market, to ensure that customers get the value they pay for out of existing reserves before any administrative increase in prices (i.e., scarcity pricing).

Demand Response

Scarcity pricing will not incentivize increased participation of DR resources in the real-time (RT) market on its own. In both the November 10 and 20, 2025 price formation meetings, CAISO suggested that scarcity pricing “motivates all available resources to respond (by increasing supply or reducing demand),” in the RT market. This comment is not supported by the evidence that the vast majority of new capacity resources built in California (or for CAISO customers) since the 2001-2002 energy crisis was procured based on forward, long-term capacity contracts backed by customers that require the capacity to bid into the CAISO energy markets under RA provisions. While there is typically a small amount of capacity available to the CAISO in exceedance of annual RA obligations – such resources usually retire unless they are able to secure RA capacity payments within a few years.

Although scarcity pricing may “motivate all available resources to respond” in markets where capacity and energy prices are baked into the energy market price, it is unclear whether that would be the case for CAISO. In terms of California DR, a significant portion of DR resources’ revenue comes from RA capacity payments and not energy market revenue. If the resource has already received an RA capacity payment, it should not need further revenue to incentivize its participation in the energy market. Likewise, energy prices alone do not typically provide enough incentive to encourage customers to curtail load through demand-side mechanisms, and most customers do not have the ability to respond quickly to price signals in the RT market, absent an automated device.

In the November 20, 2025, meeting the CAISO also stated that “if demand was price sensitive in the RT it could negate the need for scarcity pricing mechanisms.” Multiple stakeholders questioned the ability of demand to respond to price signals. Some stakeholders recommended DR issues be addressed first. We agree with CAISO that DR participation in RT could negate the need for scarcity pricing and echo the stakeholders’ comment that enhancements to DR market participation should come before developing a new scarcity pricing mechanism. California is already making major investments in Demand Response. The CPUC has authorized nearly two billion dollars for the IOUs’ 2023-2027 DR portfolios alone. And this does not include the DR investments at the other LSEs or the DR that LSEs procure separately through RA contracts. Additionally, CAISO already has market mechanisms – the ramp-up and ramp-down products – that allow for finely-tuned price-responsive resources to quickly react to load fluctuations. Adding another product on top of existing ones may pay for the same service from the same resources.

ED staff is concerned that introducing a new scarcity pricing mechanism would create duplicative efforts and unnecessary costs for Californians. It could also contravene established DR programs that are legislatively mandated and implemented by the CPUC. Market integrated economic and emergency DR programs incentivize customers to reduce demand and eliminate or improve scarcity conditions.?The goal is to prevent high market prices and the resulting cost impacts to ratepayers. DR programs are paid for by Californians either in rates or through general funds. To increase prices using a scarcity pricing mechanism would require California ratepayers to double-pay for these resources: first with the program costs that are charged in rates or general-funded, and then with the higher scarcity prices charged to load in the CAISO market.

Furthermore, scarcity pricing should not be adopted until the current CPUC proceeding(s) has/have fully considered how DR initiatives should be modified to interact with forthcoming dynamic rates. Unlike scarcity pricing for energy market prices, dynamic rates provide real opportunity for today’s curtailable load to respond to a higher fidelity price signal that includes multiple value streams – including marginal generation, distribution, and transmission capacity – and dynamic rates do so with an overall California ratepayer cost impact that is potentially lower than scarcity pricing impacts through revenue-neutral rate design. Incorporation of dynamic rates with day-ahead hourly prices has a higher likelihood of inducing incremental load response than RT market scarcity pricing, when considering the current ecosystem of DR programs in California. The likelihood of new load responding to real time scarcity pricing depends on RT pricing signals being available to curtailable load, which is mostly not the case today.

VOLL and Resource Adequacy

Based on the latest two price formation meetings, CAISO staff seem to suggest that Value of Lost Load (VOLL) is the scarcity value that CAISO would likely use for comprehensive scarcity pricing. VOLL is entirely divorced from the cost of providing the actual product of service. ED staff opposes applying such a VOLL mechanism: It is unproven, could lead to extremely high prices under certain circumstances, and is inappropriate for the CAISO market. A scarcity value based on VOLL would run counter to CAISO’s obligation to reduce overall costs to customers under Pub. Util. Code § 345.5(b)(2).

A VOLL would essentially replace the existing hard offer cap of $2,000 with higher values based on the potential “harm” to customers (“lost load” instead of the cost of energy service). ?The Midcontinent Independent System Operator (MISO) has proposed establishing a new "Pricing VOLL" of $10,000/MWh and a new "System VOLL" of $35,000/MWh. Applying VOLL values of a similar magnitude to CAISO could lead to excessive increases in prices and higher costs for California customers. For example, even if only 10% of bids in CAISO were to clear at the proposed MISO VOLL values, a VOLL of $10,000/MWh would result in?$45 million in total market costs for just one hour, while a VOLL of $35,000 would result in?$157 million in total market costs for just one hour.6 Even if these costs only occurred for one hour in a year, they would solely benefit existing suppliers (pure producer surplus) and would be unlikely to induce a single new MW of reliability infrastructure to be built for the market.

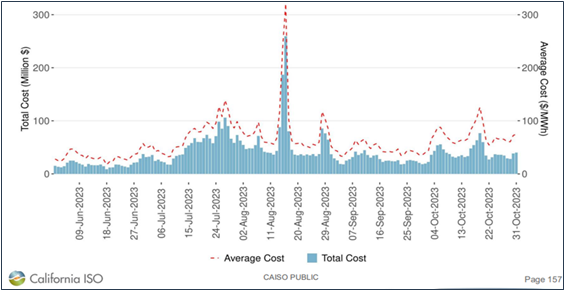

The magnitude of scarcity market events causing producer surplus impacts can be illustrated using a real-world example: On August 16, 2023, CAISO called a?DR event. CAISO then raised the bid cap?from $1,000/MWh to $2,000/MWh, which led to prices spiking. The highest bid became the clearing price for the entire market (not just the extra MWs).?Even with prices only rising to $1,200 MW for a few hours, it had a profound effect on the market.?While on a typical day total wholesale market?costs usually range from?$40-$70 million, total costs on August 16, 2023,?reached over $250?million.

If a VOLL had been in place during that August 16, 2023 event, total market costs would have reached into the?BILLIONs?of dollars.

Moreover, VOLL would only make sense for wholesale electricity markets that do not include RA programs or markets – such as ERCOT – because such markets enable generators to capture the full cost of meeting reliability through energy prices. In contrast, LSEs in the CAISO BAA participate in the CPUC’s RA program (or self supply their own RA as their own ‘Local Regulatory Authority’) and generators receive significant revenues for providing reliability (via their availability) from capacity payments from bilateral RA agreements – well in advance of entering the CAISO markets. Generators with a Must Offer Obligation (MOO) in CAISO receive energy revenue through the integrated forward market (real-time and day-ahead) and through RA capacity payments. The RA capacity payments capture the cost of reliability and fully cover the difference between costs and energy market revenues, which would then essentially be double counted through a costly VOLL. The RA capacity payments already provide the “missing money” that the energy market revenues do not provide. If CAISO were to allow prices to increase up to a VOLL, the CPUC would then need to consider whether to eliminate the RA capacity payments to avoid double-paying for VOLL both in RA capacity and CAISO scarcity pricing.

The CPUC’s RA program establishes an RA requirement to meet a PRM based on loss of load expectation calculations. In doing so, the CPUC RA program already establishes demand in the bilateral RA market for capacity to provide reliability at a level that should ensure avoiding load losses.?Additional capacity requirements over and above the CPUC’s RA requirements should be handled as extreme and rare events (well outside of planning models): There is no need to make a “market product” using VOLL to pay for their availability for extreme events.

Finally, the calculation of a VOLL metric is based on numerous assumptions concerning how customers value electricity reliability, and each of these assumptions will differ depending on the market in question, customer class, type of market, econometric issues, etc. It would be difficult, if not impossible, to develop a VOLL metric that fairly and accurately applies to all the non-homogenous customers spread across a climatically and geographically diverse regional market.